AI-Powered Educational Ecosystem

A patent-pending ecosystem reimagining how a university of 135K+ students learns, enrolls, and operates — replacing rigid courseware with adaptive pathways across 24 months of design and development.

My Role

- Strategic UX vision for an ecosystem of 5 products, 98 workflows, and 6 user types over 24 months

- System analysis, user flows, wireframes, prototypes, visual design, and architecture documentation — 200+ screens across multiple iterations

- Lead designer for communications sub-system

- Conducted 20+ contextual interviews with university staff

- Stakeholder presentations to leadership across a ~50 person initiative

Results

Founded Team

Stood up an entire product development team from scratch and delivered software in less than 2 years

Released POC & Alpha

Designed, developed, and tested a proof of concept, alpha release, and started beta release

Applied For Patent

I was one of the key contributors to the patent application

Confetti Design System

Released a robust design system to establish system-wide UX and UI

The Challenge

SNHU faced a crisis on multiple fronts. Declining enrollment signaled students’ growing doubts about the value of increasingly expensive degrees. Those who did enroll often found themselves forced to retake courses for knowledge they already possessed—wasting time and money. Rigid term-based schedules left no room for flexibility, so when life circumstances changed, dropping out became the only option. Behind the scenes, course development moved too slowly to keep programs relevant, and manual processes had pushed both staff and infrastructure to capacity. The university’s traditional model was breaking under its own weight.

The Goal

Our goal was to rebuild SNHU’s entire educational infrastructure from the ground up – creating systems that valued learners’ existing knowledge, adapted to their lives rather than forcing rigid schedules, and could scale without overwhelming staff. This meant reimagining everything: how students enrolled, how they learned, how courses were created and delivered, and how achievement was recognized. Not incremental fixes to a broken model, but a complete rethinking of what modern education technology could be.

The Constraints

The university had never developed software. We had no existing platform to build from, no institutional knowledge of product development, and no established design patterns.

Everything was being rethought at once: learning models, course architecture, student achievement frameworks. Meanwhile, 135,000+ students needed uninterrupted access to their education throughout the entire transformation.

Competitive Landscape

I have been working with Learning Management Systems for more than 20 years. They are the backbone of training and education worldwide — systems like Cornerstone, Workday Learning, Blackboard, Moodle, Canvas, LinkedIn Learning (formerly Lynda.com), and earlier platforms like Docent and Saba that have since been absorbed by larger players.

Despite decades of evolution, most LMS platforms share the same foundational architecture:

- User Management – Learners, instructors, and administrators, each with role-based access and permissions.

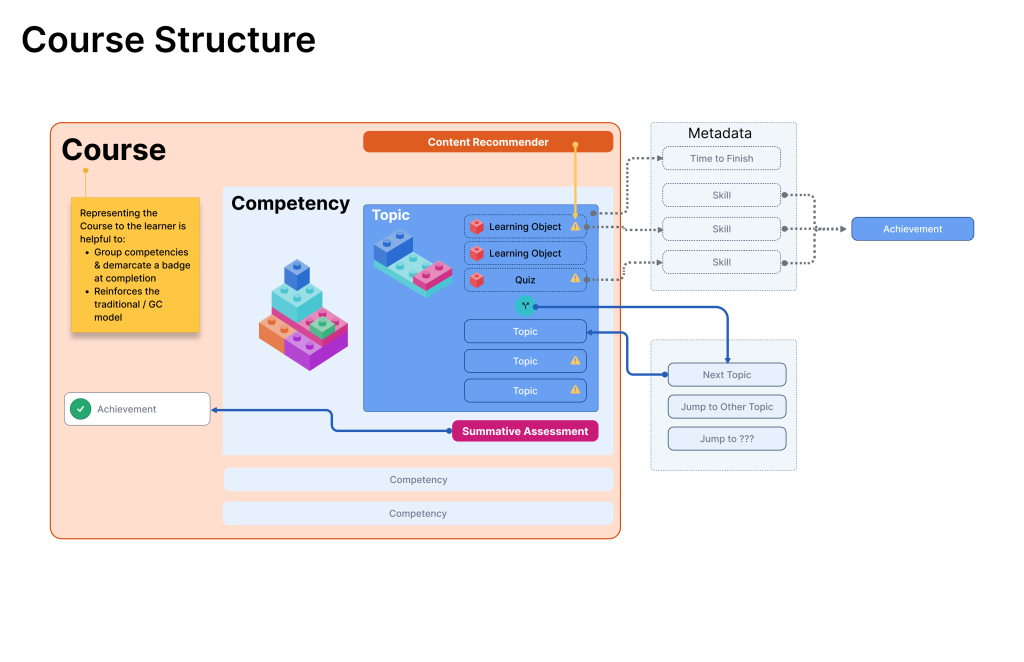

- Courses – Pre-authored packages of educational content, typically structured as a linear sequence of modules, lessons, and assessments. Most are built to content standards like SCORM or xAPI, which allow them to be reused across systems but not dynamically adapted within them.

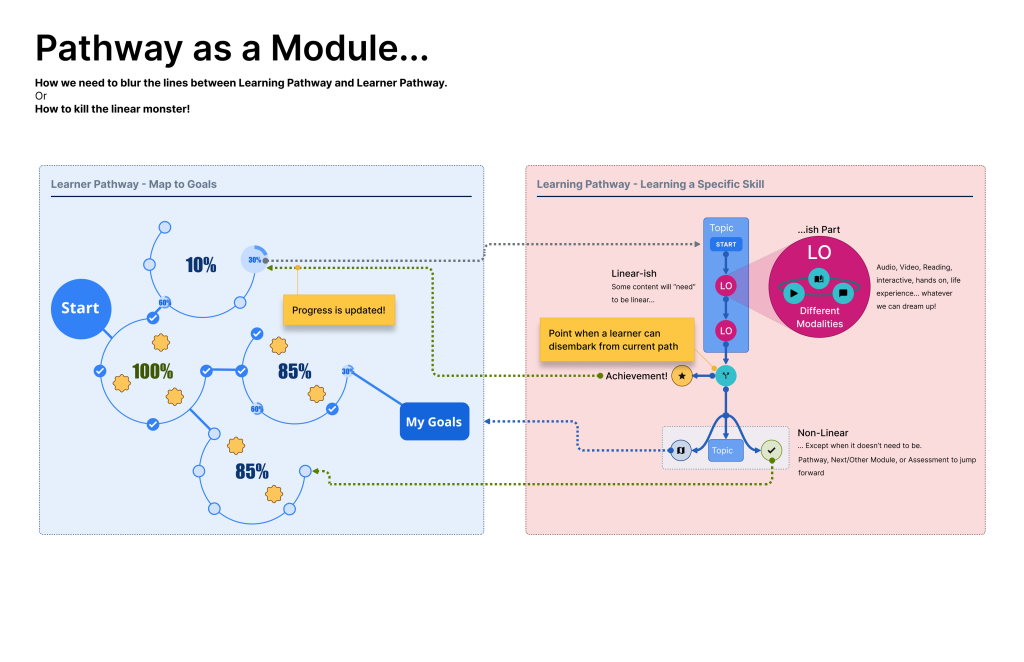

- Pathways – Predefined sequences of courses leading to a credential or achievement. Some systems offer limited branching — skipping a module if a pre-test is passed, or repeating content after a failed assessment — but the logic is manually authored and static. No mainstream LMS dynamically restructures a pathway based on a learner’s changing circumstances.

- Learning Interface – Where learners consume content, complete assessments, and progress through courses and pathways. Interaction is largely passive: watch, read, answer, advance.

The result is a system optimized for content delivery and compliance tracking, not for modeling the complex, non-linear reality of how people actually learn. Courses are rigid. Pathways are linear. And when a learner’s situation changes – they drop a course, transfer credits, or demonstrate competency outside the system – the LMS has no way to absorb that information and adapt.

Our Users

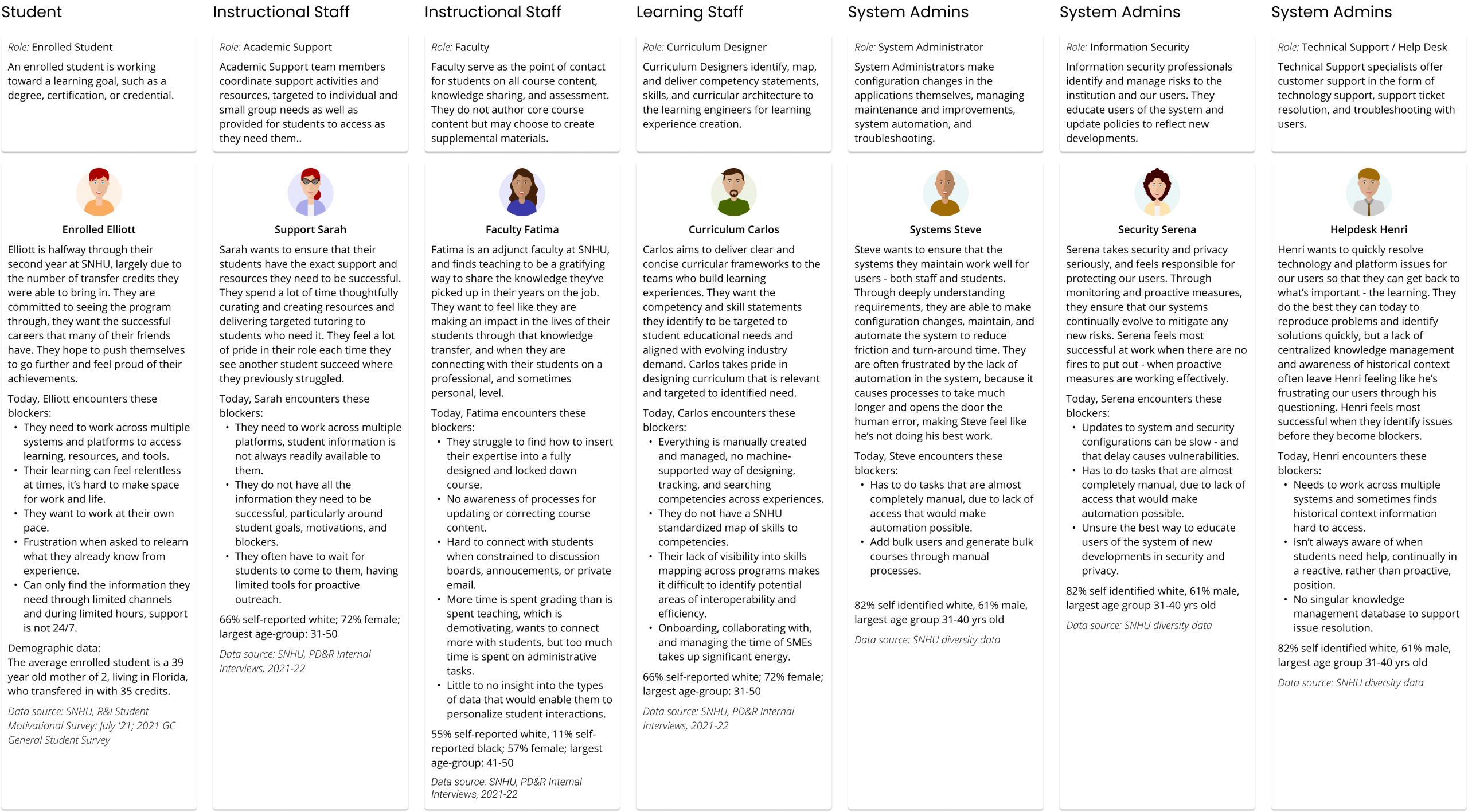

The ecosystem needed to serve every user type in the university:

| User Type | Primary Needs |

|---|---|

| Learners | Take coursework, earn achievements, manage their educational journey |

| Instructional Staff | Review learner progress, provide course assistance |

| Assessment Staff | Review and approve/reject assessments, communicate feedback |

| Academic Advisors | Track pathway progress, guide academic decisions |

| Learning Experience Engineers | Build courses, associate metadata, create pathways |

| System Administrators | Manage users, access, and system operations |

Research & Discovery

A dedicated research team conducted user and staff interviews and developed contextual studies to guide our approach. In addition, each product team conducted their own user and stakeholder interviews for their portion of the system.

As an example, I participated in over 20 contextual interviews with university staff, including sessions with the counseling team. We observed their workflows, asked about pain points, documented the systems they used, and mapped how they interacted with learners. What we found was revealing:

- Most of their process lived in personal notes scattered across multiple systems – there was no single source of truth

- There was no standardized workflow; each counselor had developed their own methods

- A single student action like dropping a course could cascade through their degree pathway, potentially adding years to graduation — and counselors had no tools to model or predict these impacts – and Students were completely reliant on staff to gain this insight

These findings directly shaped core features of the ecosystem, including the Glidepath system’s pathway modeling and the real-time progress tracking that gave counselors and students visibility they’d never had before.

The Solutions

Rather than patching a failing system, we designed a fundamentally different approach to education. AI would power personalization and streamline administrative processes – not generate content, but guide students through complexity. Credit for Prior Learning would finally recognize what students already knew, eliminating redundant coursework. The entire model shifted from degree-oriented to goal-oriented – students would pursue specific competencies and outcomes, not arbitrary credit hours. And critically, we removed the rigid term structure that forced students to choose between life circumstances and their education, replacing it with flexibility that adapted to their reality.

The full UX architecture for the learner experience – from the Guide Me onboarding flow through Credit for Prior Learning, adaptive pathways, and achievements – is covered in the Learner UX Architecture case study.

An Intelligent Approach to Artificial Intelligence

While competitors rushed to use AI for content generation – creating entire courses, tests, and learning materials – we saw the risk. AI hallucinations in educational content aren’t just problematic; they’re dangerous.

We took a different approach entirely: don’t use AI to create content. Instead, we applied machine learning to administrative and guidance systems where it could genuinely help students navigate their education. Our machine learning models processed vast amounts of transcript data, enrollment records, and competency frameworks – with human oversight at every learning phase to catch errors before they impacted students.

Three specific applications: accelerating transcript evaluation from weeks to days, suggesting personalized learning paths based on each student’s background and goals, and intelligently mapping coursework to the competencies they need. The AI handled the complexity of matching prior learning to requirements, not the learning itself.

Declining Enrollment / Value Solutions

Credit for Prior Learning (CPL)

Machine learning evaluates students’ prior experience – work history, certifications, previous coursework – and maps it directly to competencies in their program. This eliminates redundant classes while dramatically reducing the manual work that previously overwhelmed registrars. The result: students save time and money, the university unlocks scalability, and most importantly, credit can be applied throughout a student’s journey, not just at enrollment.

Goals vs. Degrees

Instead of locking students into fixed degree requirements, pathways adapt to their actual career goals. Students see projected outcomes – expected income, career opportunities, time to completion – before committing to a path. The system suggests alternatives when they make more sense: a targeted certificate program or boot camp might get someone to their goal faster and cheaper than a full degree. As students accomplish milestones, their pathways recalculate, always optimizing for their evolving objectives.

We went further, testing a fundamental change to how university credit works: One Competency – One Credit (1C-1C). Instead of forcing students to complete entire three-credit courses, they could earn single credits by demonstrating individual competencies. This granular approach meant students could make progress in smaller, more manageable chunks – earning credentials piece by piece and stacking them toward certificates, degrees, or whatever goal made sense for them. It was the ultimate expression of flexibility: learn what you need, when you need it, and get recognized for it immediately.

Retention Through Flexibility

We eliminated the rigid term structure that forced students to drop out when life happened. Students can pause and resume based on their circumstances without penalty. Progress is measured through demonstrated competency, not seat time or attendance. Intelligent nudges keep learners on track according to their own preferred schedules – the system adapts to them, not the other way around.

Course Development Innovation

Traditional LMS platforms lock content into rigid structures that become outdated quickly and require massive effort to maintain. We designed courses as modular, reusable components instead. Every piece of content carries rich metadata and tagged concepts, so updates to a single concept automatically propagate wherever it appears – update ‘photosynthesis’ once, and it updates across biology, environmental science, and agriculture courses. AI generates alternative formats from master content – audio versions for accessibility, video explanations for visual learners, localized versions for different regions, all from the human-created and validated content – without requiring faculty to recreate everything manually. The result: content that stays current, adapts to different learning styles, and scales across the entire university without multiplying the maintenance burden.

More details in the Authoring Platform case study.

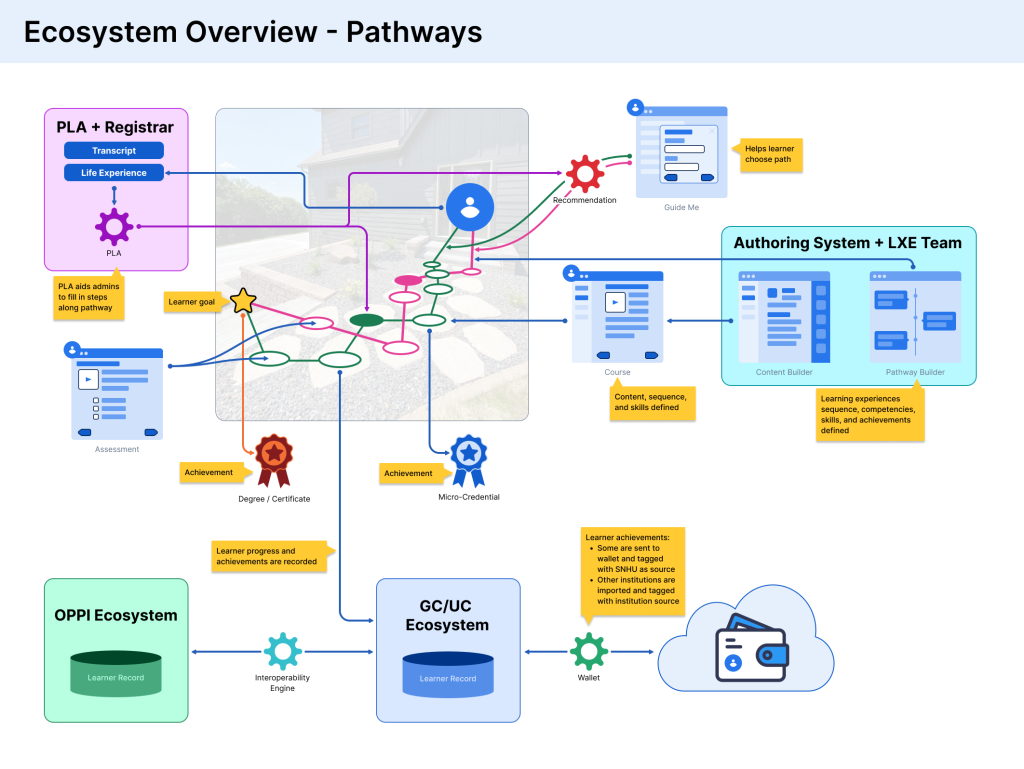

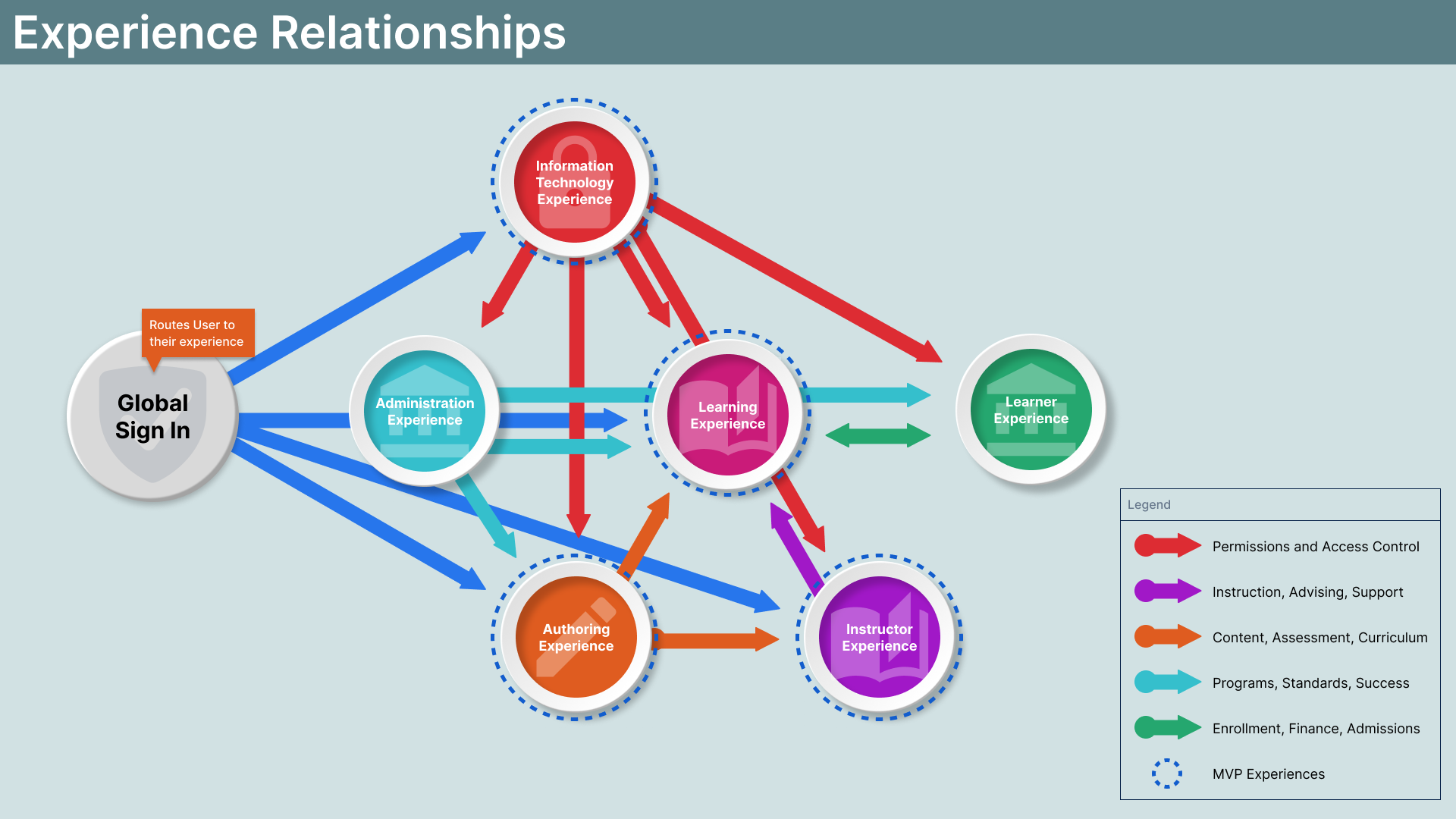

Ecosystem Architecture

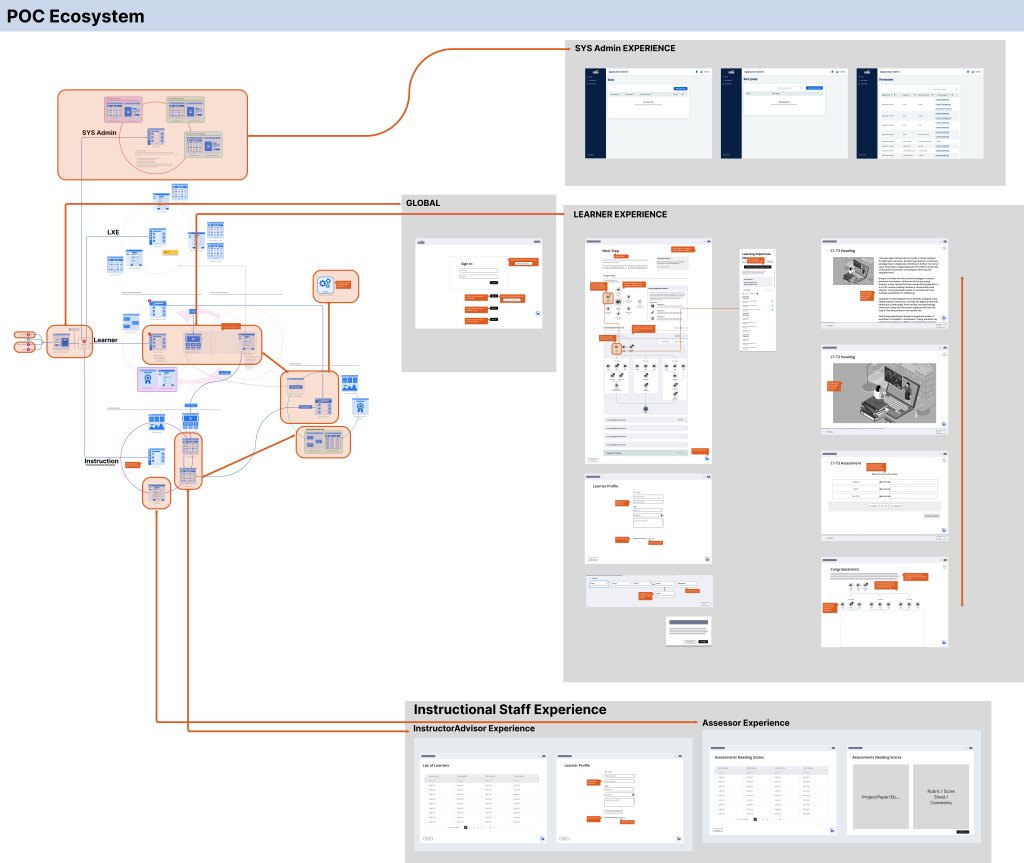

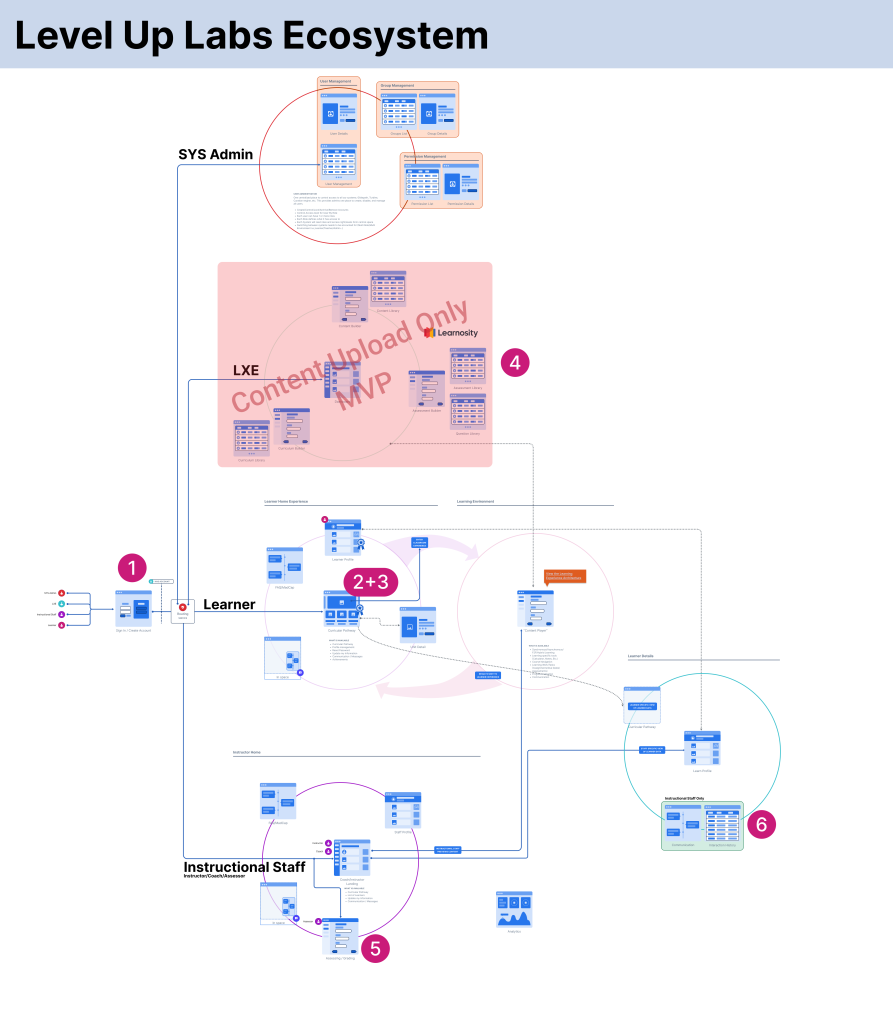

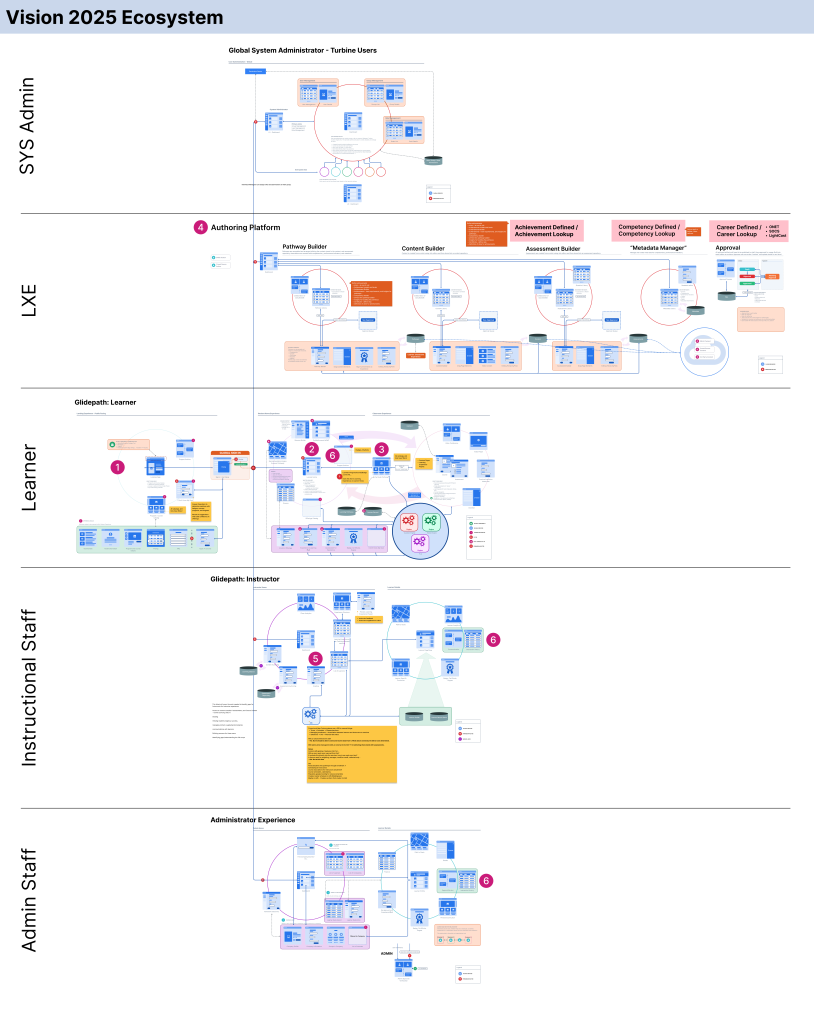

I mapped the complete system architecture – every workflow, every touchpoint, every connection between components. These high-level designs became the guide for individual teams working on enrollment, learning, assessment, and credentialing, showing them how their piece fit into the larger whole. Without this view, teams would optimize for their own features at the expense of the overall experience.

I also designed how we’d build it. The Proof of Concept phase tested the most critical paths end-to-end – could a student actually enroll, get credit for prior learning, access coursework, and earn credentials? We proved the fundamental flows worked before investing in the full build. Just as importantly, this phase stress-tested our development process itself. The organization had never built software before, so we needed to learn how to work together before scaling up.

Each subsequent phase added layers to what we’d already built and validated. Gradual, agile expansion rather than big-bang deployment. This approach let us course-correct early when mistakes were cheap to fix, not after we’d built the entire system on a flawed foundation.

- Public Site & Guide Me Experience – AI-assisted onboarding matching learners to optimal pathways

- Learner Home – Unified dashboard for managing the entire educational journey

- Learning Pathways – Personalized, adaptive sequences powered by ML

- Authoring Platform – Meta-data driven content creation (see separate case study)

- Achievement System – Competency-based credentialing with stackable micro-credentials

- Support Systems – Integrated communication and advising

Success Metrics

What we proved

- POC – We validated that the core architecture functioned end-to-end and users could navigate the primary flows.

- System Validation Alpha – End-to-end testing of all system components with internal users completed

- Patent – We filed a patent on behalf of the University for our system design

- Team and Process – We stood up a software development team from scratch and delivered software.

By the Numbers

| 5 | Products designed across the ecosystem |

| 98 | Workflows documented |

| 6 | User types served |

| 200+ | Screens designed across multiple iterations |

| ~50 | Team members across the initiative |

| 8 | Core UX team members |

| 24 | Months from kickoff to discontinuation |

What was planned

- System Validation Beta – End-to-end testing of all system components with real users

- 1C-1C (One Competency – One Credit) – Testing a revolutionary model where each competency equals one credit, allowing learners to earn credits in smaller chunks and stack toward larger credentials.

Patent

I was a primary contributor to the SNHU patent application:

“Technologies and services to deliver customized and responsive learning pathways and related systems and methods”

Co-inventors: Joel Cory, Michael Moretti (Technical PM), Lisa Hodge (UX Writer)

Reflections

What We Proved

Before the project reached full deployment, we validated core assumptions through a working POC and alpha release. Testing critical flows in the POC phase before building everything saved us from expensive mistakes and gave the team confidence the architecture could scale. We filed a patent (USPTO 18/313268), established a functioning cross-team design and development practice, and demonstrated that the ecosystem approach could unify previously disconnected university systems.

SNHU ultimately closed large portions of its business due to financial pressures – declining enrollment, costs from acquisitions that didn’t return on their investment, and sweeping budget cuts led to the layoff of multiple departments, including ours. The irony wasn’t lost on us: the very problems driving the university’s financial difficulties – declining enrollment, poor retention, manual processes that couldn’t scale – were exactly what we were building solutions for.

What I Learned

This project pushed me in ways I hadn’t experienced before. Architecting an entire educational ecosystem from scratch – not iterating on something existing, but envisioning how dozens of interconnected systems would work together – required a different kind of thinking. I learned to hold the complete picture in my head while designing individual pieces that teams could actually build.

Just as challenging was helping a university with no software development culture learn to build products. It wasn’t enough to design great systems – I had to help the organization understand how product development actually works, from agile methodologies to cross-functional collaboration. The human and organizational challenges were as complex as the technical ones.

The phased approach proved invaluable. Testing critical flows in the POC phase before building everything saved us from expensive mistakes and gave the team confidence they could actually execute. I learned that validation isn’t just for users – it’s for the organization building the product.

This project reinforced what I’d learned at PowerSchool – that my strength lies in the space between UX architecture and technical advisory. Not quite product management, not quite engineering, but the translator who helps design and development speak the same language. At SNHU, I refined this approach at a much larger scale, bridging gaps across more teams and more complex systems than I’d tackled before.

And finally, I saw firsthand how machine learning could transform operations that previously required armies of people – not by replacing humans, but by handling the complexity that overwhelmed them.

Looking Forward

This project represents some of my most ambitious and innovative work. While it didn’t reach production, the thinking, architecture, and patent-pending innovations demonstrate my ability to tackle transformational challenges in educational technology.

Related Projects

- Learner UX Architecture – Deep dive into the learner experience

- Authoring Platform – Content creation system design

- Achievement Process – Competency-based credentialing